Eliminating Fixture Effects from Embedded Measurements

July 29, 2022Introduction

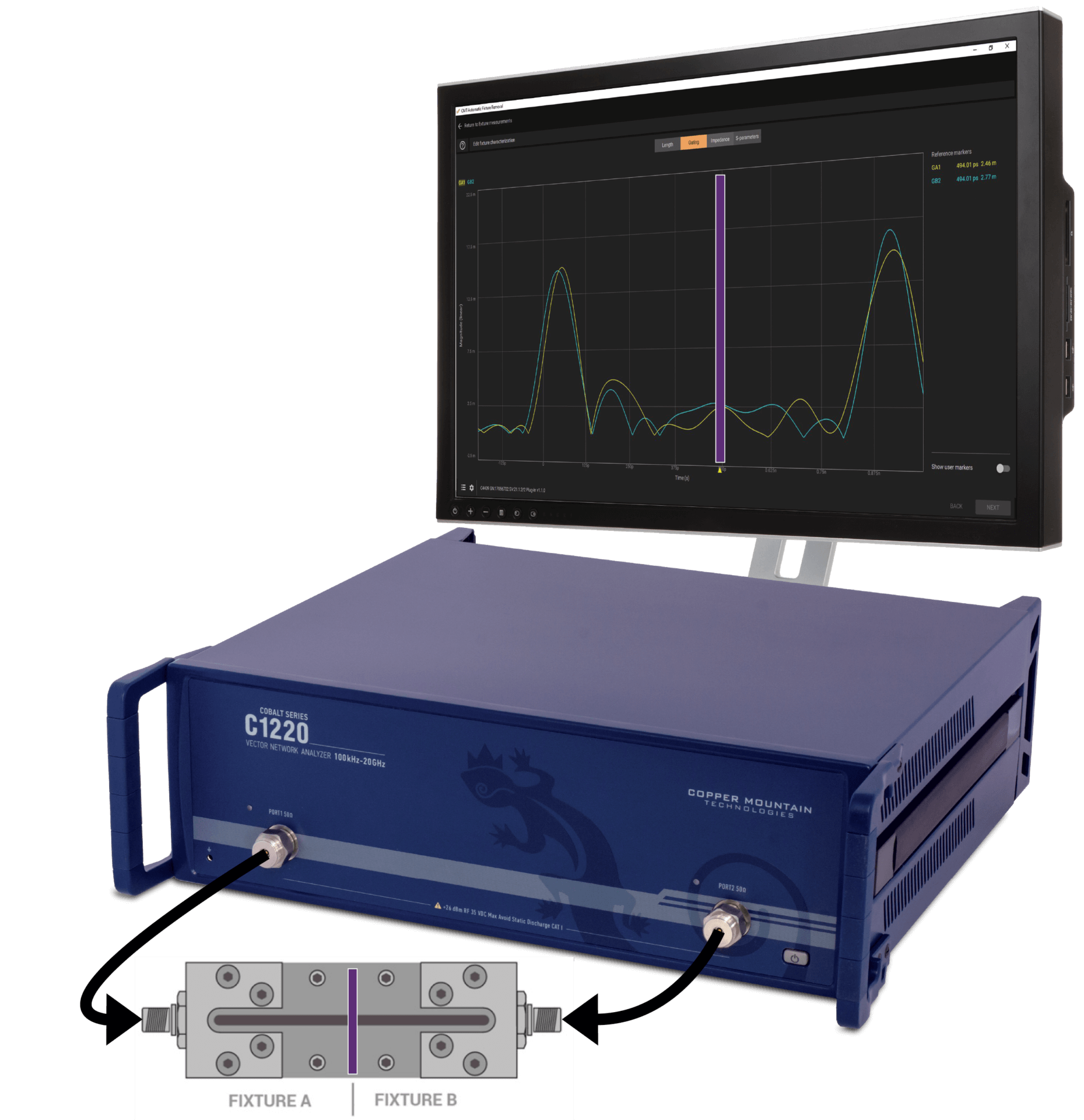

It is often necessary to measure a Device Under Test (DUT), which is mounted on a fixture attached to a printed circuit board. A vector network analyzer (VNA) is easily calibrated to the ends of a pair of test cables and may then be attached to the fixture containing the DUT. However, this measurement will include the reflections and phase delays of the connectors and traces on the circuit board and is not an accurate measurement of the DUT alone.

Figure 1 – DUT on Fixture

There are two methods to isolate the DUT measurement within the fixture: Port Extension and De-Embedding. Port Extension moves the reference plane from the original calibration point to the DUT as defined by the delay t1 and t2, as shown in Figure 2. Compensation for the loss on the fixture may also be enabled. This will be a linear loss function specified between two frequency points. Port Extension does not compensate for reflections caused by connectors or traces which do not exhibit a 50Ω characteristic impedance. If the connector has a 10 dB Return Loss, it will be impossible to measure DUT Return Loss better than this.

The phase errors due to the delay of the connecting lengths in the fixture may be corrected using Port Extension. After performing standard calibration on the test cables, the delays t1 and t2 in Figure 2 can be entered in the Port 1 and Port 2 Extension fields in the VNA menu. If the delays are unknown, a short circuit may be applied at the pins of the DUT and the extension values adjusted until the measured S11 and S22 phases are mostly centered at 180° on the Smith Chart.

Figure 2 – Fixture Delays

Port Extension

Port Extension corrects the phase measurement of the DUT and can also compensate for loss of the connecting lines.

For example, calibration was performed on the end of a test cable and then attached to a PCB with two connectors with a 2.75”, 50Ω microstrip trace between them. When measured from 100 kHz to 8.5 GHz and displayed in Polar mode, one would see the measurement in Figure 3.

Figure 3 – 2.75″ Open Trace on PCB

The measurement is smooth with no discontinuities or visible resonances. At 100 kHz, the phase is very near zero as one would expect for an open circuit. But as the frequency increases, there is an additional phase difference as the stimulus signal from the VNA traverses the open trace twice, once to the open circuit and then back again to be detected by the VNA. The reflection sees a total distance of 5.5”. Marker 2 at 600 MHz is at nearly 180°, or a half period, which is 833 pS round trip. Note how the reflection measurement spirals in as the frequency increases. This is due to the increasing Insertion Loss in the circuit board trace. If a 416 pS port extension is dialed into Port 1, the result is the measurement in Figure 4.

Figure 4 – 416 pS Port Extension enabled

The measurement is now somewhat compensated up to about 5 GHz, but from 5 to 8.5 GHz, there is an additional delay, or dispersion, due to the properties of the circuit board material, and the phase moves clockwise once again. There are also retraces in the response above 5 GHz, which are likely due to higher order modes in the signal propagation. The Loss function may be used to set a linear loss compensation between any two frequency points. With the Loss settings shown in Figure 5, the new measurement in Figure 6 is closer to the circumference of the Smith Chart.

These results are not very good over such a broad range, and there would be a great deal of phase error at higher frequencies if a broadband measurement were required. But if it were only necessary to measure over a narrow bandwidth, the extension could be successfully optimized. For instance, for Wi-Fi frequencies from 2.412 to 2.472 GHz, the phase error would only be a few degrees from one end of the band to the other.

Port Extension amounts to a simple, linearly frequency-dependent rotation of the measured S-Parameters about the center of the Smith Chart with some Insertion Loss correction. It is a useful software feature in many circumstances, but the method has its limitations.

Figure 5 – Port Extension Settings with Loss

Figure 6 – Port Extension with Loss Compensation

While Port Extension corrects the delay and phase to the DUT and may also correct for a certain amount of loss, de-embedding provides a full correction, point-by-point over the entire frequency range.

TRL

TRL might be used to de-embed the DUT on a PCB fixture. This method would require a connectorized Thru line with a length equal to the input and output traces from the DUT to be created. Then another connectorized line like the thru but longer by 90 degrees, the match line, would be added. Lastly, two connectors would be added, simply shorted to ground. These are the Reflects. If the delay of the Thru is set to zero in the VNA calibration kit definition, then after calibration, the reference plane will be set in the middle of the Thru. Subsequent measurements of the DUT will then be referenced to the DUT input and output pins.

There are two issues with this sort of calibration technique. First, the match line will only be useable where it is 20 degrees to 160 degrees longer than the Thru at any given frequency. The useable bandwidth of the fixture will therefore be confined to between 0.22 * Fc and 1.78 * Fc, where Fc is the center frequency where the match line is exactly 90 degrees longer than the Thru line.

Secondly, the match line must have pristine Return Loss, better than 25 dB, including connector reflections. The Return Loss of this line sets the “floor” for Return Loss measurement of the DUT. Return Loss measurements which appear to be less than the Return Loss of the match line would be meaningless.

SOLT

It is also possible to create Open, Short, Load, and Thru artifacts on a PCB fixture. The Open and Short standards will have lead-in lines if the traces connect to the input and output of the DUT to set the reference plane properly. Normally, the calibration kit definitions entered in the VNA for a homemade calibration kit like this would use default entries that assume no Open capacitance, no Short inductance, a perfect 50Ω Load, and a Thru. These assumptions might hold to 1 or 2 GHz. The Short inductance can be made quite small, and the Thru can be accommodated using the unknown Thru technique, so its loss is not terribly important. The Open will have some fringing fields at the endpoint, though, which amounts to a capacitance that introduces some error. The Load will be very difficult to produce on a circuit board. A Return Loss of at least 30 dB is necessary, which is extremely difficult to attain. The best implementation might use four 0402, 200Ω Ohm resistors at the end of a trace, two perpendicular and the other two angled off the end. This reduces lead inductance which still exists, even in 0402 resistors. At the same time, the capacitance to ground from the connection pad is a problem.

SOLT is a viable alternative for calibration on a PCB, but the design is quite difficult and will likely only be suitable to a few gigahertz of bandwidth. High-quality end-launch connectors would be required to reduce errors due to reflection and ensure repeatability.

De-Embedding

A fixtured DUT may be represented by an unknown S-Parameter matrix surrounded on each side by matrices A and B representing the effects of the fixture:

![]()

Equation 1

Where S’ represents the measured value of S modified by the fixture input and output, A and B. S-Parameters cannot be multiplied in this fashion. However, with conversion to Transfer parameters (T), it is possible to do so. The conversion from S to T is simply:

![]()

Equation 2

where determinant ![]()

And the reverse is:

![]()

Equation 3

where determinant ![]()

If we can accurately measure the 2-port S-Parameters of each side of the fixture, A and B, then we can de-embed S from Equation 1 by inverting the Transfer Parameters. Then simply:

![]() where Tm is the measured Transfer Parameters

where Tm is the measured Transfer Parameters

Equation 4

If the S-Parameters of sides A and B are known, the associated Touchstone files may be loaded into the VNA. In S2VNA or S4VNA software, this is found in Analysis/Fixture Simulator/De-Embedding. Point to the appropriate files for the ports in use, enable De-Embedding, and enable Fixture Simulation. The VNA will invert the supplied S-Parameters as in Equation 4 and give the measurement of the DUT alone. In the SNVNA menu, look under Analysis/Fixture/De-Embedding for this feature. De-Embedding is a feature included in all Copper Mountain Technologies VNAs at no extra cost.

But how are the S-Parameters of the fixture obtained? It may be possible to directly measure the two sides if they are connectorized. If they have non-coaxial interfaces, one might have to use a direct connection using a piece of cable, but this piece of cable would need to be characterized and de-embedded as well, which greatly complicates matters. Fortunately, the Automatic Fixture Removal (AFR) software may be used to characterize fixture effects and apply appropriate de-embedding to enable accurate DUT measurement.

Automatic Fixture Removal Software

The AFR software provides three analytical methods: Time Gating, Filtering, and Bisection. Each of these methods derives the S-Parameter files of the fixturing which can then be applied for de-embedding. It can calculate full 2-port S-Parameters of sides A and B for the Fixture by measuring one side at a time into an Open or Short (1x Reflect) or by measuring both sides connected directly together (2x Thru). It is extremely important to understand how to choose the best solution.

Time Gating Method

The Time Gating method uses Time Domain techniques, and it is important to understand that the fixture size must be large enough to ensure there is enough resolution to arrive at reliable answers. Specifically, the virtual stimulus pulse utilized in time domain analysis has a rise-time associated with it. This rise-time is inversely proportional to the total bandwidth of the measurement from start to stop frequency and somewhat related to the windowing function used in the Inverse Fourier Transform. For a 100 kHz to 9 GHz measurement, this is approximately 109 pS, and for 100 kHz to 20 GHz, it is approximately 49 pS. Therefore, for successful Time Gating characterization, it is recommended that the total fixture length be greater than two rise times for 1x Reflect and twice that for a 2x Thru characterization.

As an example, for an FR4 board with εr of 4.6, the velocity factor is ![]() . Two rise times of 109 pS (9 GHz Bandwidth) would be 1.2” minimum length for 1x Reflect A and B or 2.4” for a 2x Thru characterization. At 20 GHz and 49 pS this is 0.55” minimum for 1x Reflect or 1.1” for 2x Thru characterization.

. Two rise times of 109 pS (9 GHz Bandwidth) would be 1.2” minimum length for 1x Reflect A and B or 2.4” for a 2x Thru characterization. At 20 GHz and 49 pS this is 0.55” minimum for 1x Reflect or 1.1” for 2x Thru characterization.

Fixture characterization should be carried out with as large a measurement bandwidth as possible, even if the desired DUT measurements will be at lower frequencies. Using the widest bandwidth for characterization ensures the most accurate de-embedding files will be generated, and lower frequency measurements will simply interpolate within them. That said, the fixture must have a reasonable frequency response over all frequencies of characterization. If there is significant Insertion Loss variation or if there are fixture resonances or other large reflections occurring at higher frequencies, then the upper frequency bound must be reduced to exclude them. The time domain response is calculated from all frequency data, so the presence of wild fluctuations at certain frequencies in the measurement must not be included.

The Time Gating technique may be performed in one of two ways, 1x Reflect or 2x Thru. In the first case, the fixture is measured from each side without the DUT installed such that an Open is seen by the VNA, or the end of the trace may be shorted to ground to present a Short to the VNA. If the DUT cannot be removed, it may be possible to temporarily short the end of the trace where the DUT connection is made. This is the 1x Reflect method. If a Thru trace is created which has the combined length of the input and output traces without the DUT in place, this may be measured using the 2x Thru technique with somewhat better accuracy than the 1x Reflect. These two methods are shown schematically in Figure 7.

Figure 7 – 1x Reflect and 2x Thru

Note that the 2x Thru method initially assumes the two halves of the fixture are the same length as the software determines the S-Parameters of the two halves to the mid-point. The result may be offset in time to the left or right, allowing them to be different. The overall characteristics of the transmission lines on each side must be the same, though. Also, a 1-port fixture would be measured with a single 1x Reflect measurement.

To make a Time Gating AFR measurement, start the AFR software. The Time Gating method is chosen by default in the drop-down menu on the right-hand side. Also, a fixture with two sides and one port on each side is selected by default. Fixture A or Fixture B may be unselected for 1-port characterization. The number of ports on each side may also be changed from 1 to 2 if a 4-port analyzer is being used. All port measurements are single ended. Differential characterization is not currently available in the software.

A simple 2-port, Time Gated measurement of a two-sided fixture is shown in Figure 8.

Figure 8 – Time Gating Setup

After hitting the Next button, the following screen allows the selection of 1x Reflect or 2x Thru with options. The first switch under Connect Directly shifts between these two modes. The 2x Thru method will always be more accurate than the 1x Reflect method. The diagram on the screen changes to show how the fixture measurement is configured. For A-B connected directly together, it is assumed that both sides are identical at first. A delay offset may be added on the measurement screen. This setup is shown in Figure 9. If A-A and B-B connections are selected assuming that multiple A and B sides of the fixture exist and can be connected, then the A and B sides are characterized separately using 2x Thru and need not be identical. This setup is shown in Figure 10.

Finally, one can choose the CAL ≠ DUT method. Here, two fixtures are measured. The first is a 2x Thru measurement of the fixture with sides A and B connected. The second is a measurement of the actual DUT with A and B fixture sides on the left and right sides. This is shown in Figure 11. This method might be used if the DUT cannot be removed from the fixture.

Figure 9 – A to B Characterization

Figure 10 – A to A and B to B Characterization

Figure 11 – CAL Not Equal to DUT Method

With the selection of the Time Gating method complete, one can press the Next button. In this example, the Start, Stop, and Number of Points settings are not appropriate. In Figure 12, there are problems with the VNA setup. Hovering over the yellow warning triangles will produce explanations of the issues. The software prefers to have a measurement setup where the frequency step size is equal to the start frequency such that each frequency point is harmonically related. The suggested settings on the right-hand side would have this characteristic, but the number of points is so large that the measurement would be very slow. Better to change the start frequency to 1 MHz and the number of points to 8500. The number of points should be in the thousands, perhaps 4,000 to 20,000, to ensure enough data for the program to process. If the “Ignore low pass” switch is toggled, the measurement can be made without a harmonic relationship between points. However, the impedance vs. distance will not be calculated or displayed under Edit Characterization/Impedance. This is not recommended since it is very useful to verify the impedance of fixture connectors and transmission lines to ensure the characterization will be accurate.

After changing the Start Frequency to 1 MHz and the number of points to 8500 on the VNA, the errors are resolved.

Figure 12 – VNA Setup

Pressing Next once again, the VNA calibration screen appears, and there are warnings since the VNA has not yet been calibrated.

Figure 13 – Calibration Screen

Perform full 2-port calibration on the VNA or 1-port if the fixture is one-sided, and these errors will also resolve. On the next screen, there is a choice to measure either an Open or Short or both for the 1x Reflect method or the Thru measurement for the 2x Thru method. Enabling the spline approximation in 1x Reflect may be helpful to improve the accuracy of the peak search, which finds the time delay to the Open or Short circuit. The spline works well if there is a well-defined peak due to the Open or Short circuit. If there are other artifacts nearby that clutter the area in time near the peak, the spline will not work well and should not be used. Check the Length and Gating tabs under Edit Fixture Calibration to verify this.

Figure 14 – Fixture Measurement for 1x Reflect Method

Press the Measure button to measure the Open, Short, or Thru. In Figure 14 above, note Step 1 of 2 shown on the horizontal bar for a 1x Reflect measurement. If the fixture has two sides, then one must click on this bar to go to the B side of the fixture, and another Open or Short Measurement must be made.

As long as the Open or Short at the end of the transmission line is “clean” and not distorted by nearby impairments such as coupling capacitors or any changes to the dimension of the line then the spline approximation checked above, should be enabled. This fits a spline curve to the Open or Short reflection curve and allows a more accurate estimate of its exact position through interpolation, thus improving de-embedding accuracy.

The 2x Thru method assumes that the DUT is mounted at the centerline of the fixture. If this is not the case, the reference plane may be moved by entering values in the plane offset fields. To move the reference plane 10 pS to the left, making A shorter than B, enter -10 pS in the left field and 10 pS in the right field. Alternatively, the B side of the fixture could be detached, and the reference plane can be moved by measuring the Open or Shorted side A.

If any errors occur, the menu button in the lower-left corner of the screen will bring up any error messages which may have occurred. The gear symbol to the right of the menu allows modification of various user settings and gives information on the program license.

After the fixture is fully measured, one can go back to the Fixture Connection step and hit the F9 key. This will display useful information about the fixture length and the measurement rise-time.

Figure 15 – Fixture Measurement for 2x Thru

After the measurement is complete, it is instructive to press the F9 key to view the total time delay through the fixture, the 4x risetime and the 1x risetime in the “Test Mode”. You will immediately see if the fixture length is acceptable. Finally, push Next once again to move to the Results tab. Pushing the Apply button will enable de-embedding

Figure 16 – Test Mode Screen from “F9”

using the file which the AFR software generated. The de-embedding files can also be saved for later use using the Save correction files… button. Clicking Save Setup will save the entire AFR setup so a fixture might be re-measured in the same way at some later time. The raw data may also be saved using the Save raw data button. This is the raw fixture measurement without de-embedding.

Edit Fixture Characterization

Selecting the Edit Characterization button allows one to examine the characteristics of the measurement. For a Thru measurement, the impulse shown in the Length in Figure 17 indicates the length of the fixture in time. If there isn’t a clear independent and clean reflection from the Open or Short in a 1x measurement, the spline option should be unchecked in the Measurement panel and the Open or Short measurement repeated. The Gating screen from Figure 18 shows the reflection over time across the fixture, looking from each end. The connector reflections are clear, and along the trace, there are extremely small reflections. Figure 19 shows impedance vs. distance on the connector, and these results are excellent. Connector issues would show prominently here, but the results are quite flat (in this scale) over the whole length.

The S-Parameters tab shown in Figure 20 presents the plotted S-Parameters of each half of the fixture, A and B. Double-clicking on any of the Parameters will disable them, and they will no longer be plotted. This is helpful to allow examination of each of the parameters separately.

Figure 17 – Fixture Length Screen

Figure 18 – Fixture Reflections in Time Domain

Figure 19 – Fixture Impedance vs Distance

Figure 20 – Fixture Sides A and B S-Parameters

Filtering Method

The Filtering method operation and setup are the same as Time Gating. This method uses a proprietary technique to characterize the fixture employing a hybrid of Time Domain and Frequency Domain measurements. Like the Time Gating method, it will work well with fixtures as short as four rise times and will perform slightly better than Time Gating at this minimum length. The Filtering method works in both 1x Reflect and 2x Thru modes. There should be very little variation of the characteristic impedance in the transmission lines.

Bisection Method

The Bisection method will only operate on a Thru fixture. It is unable to characterize filter halves by reflection, like Time Gating and Filtering Methods. This method has no minimum fixture length requirement since gating is not used at all. Instead, a Thru measurement is made, and the result is bisected into two halves with the reference plane set to the middle of the fixture. Again, this reference plane may be adjusted to the left or right using the calibration plane offset entries on the right side of the Fixture Measurement tab.

This method requires very good fixture Return Loss, and there will be some errors in the calculation of the Return Loss for the two halves which are generated. The two major reflections at the input and the output of the fixture experience constructive and destructive interference resulting in a periodic Return Loss, as shown in Figure 21 below.

Figure 21 – Bisection Return Loss Error

The bisected response should represent half of the fixture with half of the delay resulting in the periodicity of the Return Loss response at half the rate of the whole fixture. Instead, the mathematical process retains the periodicity of the whole fixture at about 6 dB lower level. If the Return Loss of the fixture is less than 20 dB resulting in bisected halves with better than 20 dB Return Loss, then this error in the de-embedding file will not greatly affect DUT measurement.

The Help Menu

Clicking on the Question Mark icon at each stage of the AFR measurement brings up a wealth of information pertinent to the measurement step.

Figure 22 – Help Screen Selection

Figure 23 – Help Screen for Description Stage

It is a good idea to review this information prior to choosing a measurement method and within each stage of measurement to ensure successful fixture characterization.

Fixture Suitability – A Practical Example

The Automatic Fixture Removal software is quite powerful, but there are limits to how much fixture reflection can be corrected. For best accuracy, it is best to perform AFR measurement over the broadest RF range available on the VNA. For example, the 20 GHz Cobalt C1220 VNA from Copper Mountain Technologies. If the fixture is a circuit board with SMA connectors and the DUT is intended to be tested to only a few GHz, the connectors might be rated for 6 GHz to save on cost. A 6 GHz connector will have resonant modes somewhere above 10 GHz, and the Insertion Loss and Return Loss will not be flat. Dips in the 1x Reflect measurement cause significant errors. Dips in the 2x Thru Insertion Loss will also result in errors in the created de-embedding files. If these connectors must be used, then the measurement frequency must be limited to a range where the response is reasonably flat, and the fixture will need to be somewhat longer to accommodate the slower rise-time of the measurement at lower frequencies.

Figure 24 – Fixture with 6 GHz SMA Connectors

Figure 24 shows Insertion Loss and Return Loss for a Thru made with two 6 GHz SMA connectors with a 50Ω microstrip between them. The Insertion Loss has a dip near 7 GHz and begins to roll off badly above that. The Return Loss is above 20 dB at about 5.5 GHz, so this would be the highest frequency for AFR analysis. The generated de-embedding files will be good from the lowest frequency VNA setting to 5.5 GHz. Extrapolated measurements above this will not be accurate at all.

The quality of the connector is critical for 1x Reflect characterization. During AFR characterization into an Open or a Short reflection, the signal bounces off the end and returns to the input. This returning signal should see a good source match and be received and absorbed. If the connector is of poor quality, the signal will bounce from the input and head back to the Open. This returning reflection repeatedly occurs, with each bounce reduced in amplitude, depending on the reflection coefficient of the connector and loss of the transmission line. When a well-matched DUT is measured, there is very little reflection, and returning reflection is negligible. Because of this, the application of the de-embedding file results in ripples in transmission measurements.

For these reasons, it is a good idea to use a very high-quality, precision connector, like those shown at the top of Figure 25 or the development of the de-embedding files. The fixture should be characterized with AFR to as high a frequency as possible. If subsequent de-embedded measurements are made with an economy-grade connector at lower frequencies, the results will be reasonable as long as the economy-grade and precision-grade connectors have similar characteristics at these lower frequencies.

Figure 25 – Fixtures with Precision and Economy Connectors

The Automatic Fixture Removal characterization amounts to a second-tier calibration, so it is important to have a very well-designed fixture to start with. In one recent application, a user characterized a well-designed test board on which a filter, or DUT, would be soldered and measured. Time Gating 1x Reflect was used to characterize the fixture before mounting the DUT, and the result was quite good since the connectors were of good quality and the circuit board traces were very close to 50Ω. Next, a connectorized production test fixture was designed with pogo-pins for fast insertion and measurement. The AFR software was again used to characterize the fixture, but when using the new de-embedding files, there was a significant difference as compared to the soldered DUT. The stop-bands of the filter did not go down as far as they did in the soldered fixture. It turned out that the use of pogo-pins reduced the input to output isolation of the fixture, thus limiting the depth of rejection. Some sort of metal barrier needed to be added between the input and output pogo pins to keep them from coupling to each other through the air.

It is a good idea to evaluate the quality of the fixture prior to using AFR. If a Thru standard is available, one would measure the Insertion Loss and Return Loss. Return Loss worse than 20 dB will introduce some error in the process. Discontinuities in the Insertion Loss are not acceptable. The Open or Short for 1x Reflect can be analyzed in the Time Domain mode. A poor connector Return Loss will show up right away and multiple returning reflections will be apparent as the signal bounces back and forth between the reflect and the connector. Low-Pass Step Time Domain measurement with Impedance Conversion can be used to evaluate the transmission line’s characteristic impedance after the connector. It should be within a few Ohms of 50Ω.

We can compare the responses of the two fixtures of Figure 25. The bottom fixture with inexpensive end-launch connectors has Insertion Loss and Return Loss, as shown in Figure 26. The Return Loss climbs above 20 dB after 4 GHz. The end-launch connectors are 6 GHz connectors, so it is not surprising that the response falls apart so quickly. AFR would only be able to characterize this board up to 4 GHz.

The Return Loss vs. Time shows bumps at the input and output connectors as expected.

Figure 26 – Insertion Loss and Return Loss of Economy-Grade Fixture

Figure 27 – Return Loss vs. Time of Economy-Grade Fixture

Figure 28 – Impedance vs. Time of Economy-Grade Fixture

The Impedance vs. Distance shows the impedance mismatch of connectors. The trace impedance looks reasonable at around 52Ω. Widening the trace slightly would improve this.

The Insertion Loss and Return Loss of the upper fixture in Figure 25 are much better, of course.

Figure 29 – Insertion Loss and Return Loss of Precision Fixture

The Insertion Loss increases smoothly up to 20 GHz and the Return Loss is better than 20 dB over the entire range.

Figure 30 – Return Loss vs. Time for Precision Fixture

It is difficult to distinguish the Return Loss of the connectors from the small reflections of the trace.

Figure 31 – Impedance vs. Time for Precision Fixture

The impedance vs. Time measurement is amazing. There is hardly any variation of the impedance over the length of the fixture. This fixture can be characterized by the AFR software all the way to 20 GHz. Comparing these two fixtures is instructive. A few measurements of the two fixtures established the range over which the fixtures might be used. The upper fixture of Figure 25 has great properties but was quite expensive to fabricate. It probably isn’t necessary to go to such great lengths. In the examples here, the transmission lines are reasonably accurate. The traces could be improved somewhat on the inexpensive fixture. The choice of connectors is critical though. Southwest Microwave and SV Microwave both have end-launch SMA connectors specified to 26.5 GHz and higher. These connectors would greatly improve the performance of the board, which only functions well to 4 GHz.

Resolution and Measurement Rise-Time

As stated earlier, the effective rise-time of the Time Domain measurement determines the minimum length of the connection between fixture connectors and DUT. After making an AFR measurement, pressing F9 brings up the rise-time and fixture length information as shown in Figure 16. A measurement made with insufficient resolution will produce disappointing results. Figure 32 shows the measurement of a fixture with a high enough bandwidth to give an acceptable resolution. This fixture has unacceptable connector reflection in this bandwidth, but we would have trouble observing these reflections without proper resolution.

Figure 32 – 20 GHz fixture measurement

The first peak is due to the internal mismatch of the connector. The second is due to the connector to trace launch connection. The five peaks after that are re-reflections back and forth between the first two major reflections. This is essentially a connector resonance at a frequency equal to the half-wave period represented by the delay between peaks.

This same fixture measured in a 6 GHz bandwidth gives the Time Domain response in Figure 33. The fixture is not 4 rise times in length, so the 2 rise time requirements from each end overlap. The connector reflections are not well resolved, so it is not as evident that there might be an issue with this fixture. It is important to have a full understanding of the fixture properties in order to set reasonable expectations for de-embedding with the AFR software.

Figure 33 – 6 GHz Bandwidth Fixture Measurement

Coupling capacitors on the feedline

It is not uncommon to find de-coupling capacitors in series on a DUT feedline. Many PHEMT Darlington amplifiers leak power supply voltage to their inputs, and the outputs are pulled up to VCC through a choke. These voltages must not be pulled down by other circuitry or test gear. Spectrum analyzers are often intolerant of DC voltage, so a test board for an amplifier will very likely have series capacitors on the transmission lines. The AFR software works best if the low end of the VNA frequency range is less than 10 MHz. The Low Pass mode provides twice the normal resolution by filling in a Hermetian vector, assigning negative frequencies with the complex conjugates of the reflection coefficients of the corresponding positive frequencies. This self-adjoint doubling of the data improves resolution greatly, but the original data must have a step size equal to the start frequency such that each point is harmonically related. This requires a low start frequency to ensure that the step size is reasonably small and the number of points is large enough to provide a good solution, 2,000 to 20,000 points.

For example, a 10 pF series decoupling capacitor has a reactance of 50 Ohms at 318 MHz. Because of this, it would not be possible to start analysis at a low enough frequency to implement the Low Pass mode. For this case, one would set the start frequency to perhaps 350 MHz and the stop frequency as high as possible. Set the number of points to 10,000 and on the AFR VNA Setup menu, throw the Ignore Low Pass switch, and the Sweep Points and Step Frequency warnings will disappear. The effective impulse rise-time of the AFR measurement will double, and resolution will be halved, but this is the only way to make a measurement through a small capacitor.

The Impedance tab in the Edit Fixture Characterization section of AFR will not be populated with data since the low-pass mode is required for this to be calculated.

Conclusion

Using the methods in the Automatic Fixture Removal software provides a way to characterize fixtures that could not be done in any other way. A fixture is usually not connectorized at the DUT interface, and attaching a connectorized pigtail is problematic as the pigtail itself would need to be removed from the measurement. Obtaining S-Parameters for each side of the fixture using a Reflect or Thru method is an attractive choice. The method is fast and powerful, but the user must assess the suitability of the fixture before proceeding in order to set realistic expectations. The Edit Fixture Characterization tab is helpful for this purpose. The method works best with a wide-band measurement, but the fixture may not support this, so a reduction in the bandwidth may be required to obtain reasonable results.

The AFR software operates with any Copper Mountain Technologies VNA and is available for trial. Navigate to the AFR trial section on the website or click here. Our knowledgeable sales and support teams will be happy to provide helpful information at any time. Your sales contact may be found here and support is only an email or phone call away, support@coppermountaintech.com or call +1 317-222-5400.

Appendix A – 2x Thru Time Gating Calculation

A fixture that will be measured with sides A and B connected may be modeled as in Figure 32. The overall S-Parameters of the connected A and B are shown in blue. The inner S-Parameters are for the A and B halves. This network can be decomposed using the manipulations shown. The technique is a graphical form of Mason’s Rule, see Reference 1, and Signal Flow Graphs, Reference 2.

Figure 34 – Network Decomposition of Combined A and B Sides

Then:

Equation 5 – Overall S11 of Fixture

And:

![]()

Equation 6 – Overall S21 of Fixture

Further, we assume that the Insertion Loss of the two halves are symmetrical and identical then:

From Equation 5 and Equation 6, we can write (from Dunsmore et al. Reference 3):

![]()

Equation 7

Here, S11 and S21 are the measured values of the whole fixture and S11A is obtained by bandpass gating S11 over the length of the “A” side of the fixture.

Then:

Equation 8 – S11B derived

After gating S22 on the B side to obtain S22B, we can write:

![]()

Equation 9

And,

![]()

Equation 10 – S22A Derived

We can then solve for S21A:

![]()

Equation 11 – S21A Derived

We now have all S-Parameters for sides A and B and can de-embed the fixture from the DUT measurement. Note that the square root in Equation 11 makes the sign of the S21A ambiguous. The difference between the positive and negative signs amounts to a 180° phase shift. Since we know the delay between the connector and the reflect from the S11 measurement, though, which is twice the S21A delay, we can estimate the appropriate phase and choose correctly.

Appendix B – 1x Reflect Time Gating Calculation

We assume that the connectorized fixture is terminated by an Open or a Load on the other end. If we apply a gate to the fixture which stops before the Open or Short, then we will see the Return Loss of the fixture as it would appear if the end were terminated with 50Ω. We’ll call this S11A. Next, we apply a gate to the impulse at the Open or Short. This impulse represents S21A * Γ * S12A, where reflection coefficient Γ is either 1 for an Open or -1 for a Short. We’ll call this reflection Γ2.

These two gated conditions are evident from an examination of the Return Loss vs. Time plot in the time domain, as shown in Figure 33 below. The reflection in the first gate area is due to the connector and trace alone, and the second is due to the reflection from the Open, which sees S21, the reflection, then S12 to return to the VNA or essentially, two-way Insertion Loss.

Figure 35 – First and Second Gates

We can say that this last measurement is:

![]()

Equation 12

And if we assume that S21A = S12A, then:

Equation 13

where Γ is the +1 or -1 for Open or Short

Finally, with our measured ungated S11 and from Mason’s Rule, Reference 1:

Equation 14

And re-arranging:

And we now have all four S-Parameters. Note that the square root in Equation 13 makes the sign of the S21A ambiguous. The difference between the positive and negative signs amounts to a 180° phase shift. Since we know the delay between the connector and the reflect from the S11 measurement, though, which is twice the S21A delay, we can estimate the appropriate phase and choose correctly.

Bibliography

- Mason, Samuel, “Feedback Theory – Further Properties of Signal Flow Graphs”, Proceedings of the IRE (Volume: 44, Issue: 7, July 1956)

- Stiles, Jim, “4.5 – Signal Flow Graphs”, University of Kansas, http://www.ittc.ku.edu/~jstiles/723/handouts/4_5 Signal Flow Graphs.pdf, March 19, 2009.

- Dunsmore et al., “Characterization of Asymmetric Fixtures with a Two-gate approach”, 77th ARFTG Microwave Measurement Conference, 2011

- Xie C, Xu R. A one‐port automatic fixture removal method for de‐embedding. Int JNumer Model. 2019; e2622. https://doi.org/10.1002/jnm.2622